When Barbra Streisand was 17 years old and living away from home for the first time, she set herself a goal.

“I have to become famous,” she told herself, “just so I can get someone else to make my bed.”

“I could never figure out those corners,” laughs the star, reminded of that youthful ambition.

“But, you know, it was more exciting to dream about being famous than the reality. I’m a very private person. I don’t enjoy stardom.”

It’s a lesson she learned early. When she first came to the UK in 1966, Newsweek magazine had this to say about her.

“Barbra Streisand represents a triumph of aura over appearance… Her nose is too long, her bosom too small, her hips too wide. Yet when she steps in front of a microphone she transcends generations and cultures.”

The media had an odd fixation on her appearance from the outset. She was called an “amiable anteater” with an “unbelievable nose”, who resembled “a myopic gazelle”.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

It was only when she became a superstar that the focus changed. Suddenly, Streisand was a “Babylonian queen” whose profiles were laced with superlatives – 250 million records sold, 10 Golden Globe awards, five Emmys and two Oscars, for acting and songwriting.

But the damage was already done.

“Even after all these years, I’m still hurt by the insults and can’t quite believe the praise,” writes the star in her new autobiography, My Name Is Barbra.

The book, she says, is her attempt to correct the record.

“It was the only way to have some control over my life,” she says.

“This is my legacy. I wrote my story. I don’t have to do any more interviews after this.”

Thankfully, she’s granted one last interview to the BBC from the comfort of her clifftop home in Malibu. Despite a reputation for running late, she turns up on time – even after a last-minute scramble to find her glasses.

She’s everything you could hope for: Candid, funny, approachable, slightly pampered, hugely charismatic and occasionally prone to bonkers tangents.

“I feel for flowers just like I feel for ants,” she declares at one point. “I can’t even crush them.”

Streisand’s memoir has been almost 25 years in the making. She started making notes – writing longhand, in pencil – in 1999. The finished manuscript is almost 1,000 pages long and heavy enough to be used as a weapon.

The star claims her “memory is fickle” but the book is crammed with delicious details of backstage arguments, bewildered suitors and at least one incident of falling off a London bus.

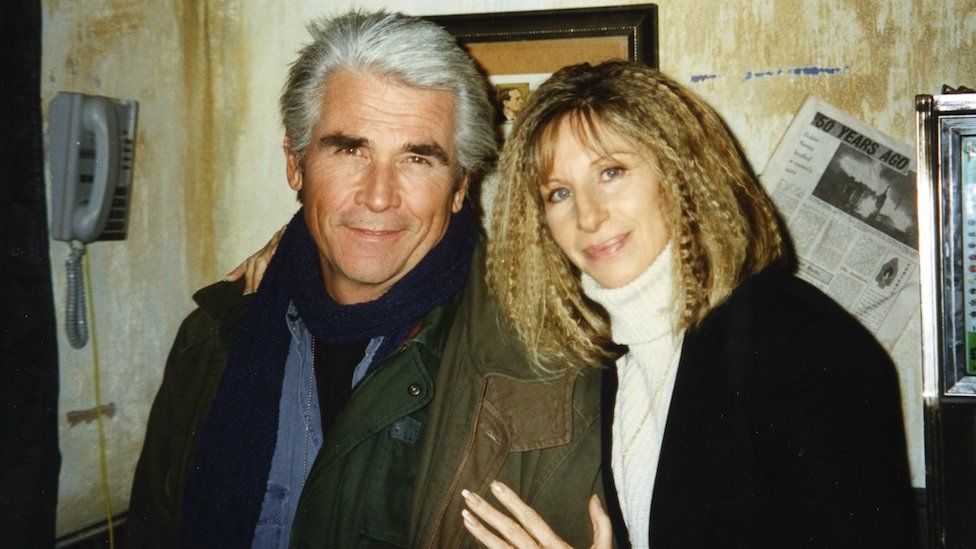

She talks about cloning her favourite dog, and signing into hotels as “Angelina Scarangella”; then reveals that her marriage to James Brolin was the inspiration for Aerosmith’s I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing.

Meanwhile, her encyclopaedic recall of every meal she’s ever eaten will leave you ravenous. The book lists mouth-watering menus of molten chocolate cake, New York pizza slices, soft-shell crabs, honeydew melon, turkey sandwiches with Branston Pickle and (her favourite) Brazilian coffee ice cream.

“I’ve loved food ever since I was a kid and lived in the projects,” she admits. “We had a tiny kitchen and I would love to bake white cupcakes and put on dark chocolate icing.”

Streisand grew up in Brooklyn, and one of her earliest memories is singing in the stairwells of her apartment block.

“I was only five or six years old, and my little girl friends and I used to sing together in the lobby. The acoustics were like a built-in echo. It was a great sound.”

But home life was hard. Her father Emmanuel died of a cerebral haemorrhage when Streisand was 15 months old, leaving the family in poverty. As a child, she turned a hot water bottle into her doll, hugging it at night as she fell asleep.

When her mother remarried a couple of years later, things didn’t improve. Streisand’s new step-father, a used car salesman, was distant and cruel.

“I don’t remember ever him talking to me or asking me any questions… How am I? How is school? Anything,” she says.

“I was never seen by him – or by my mother, either. She didn’t see my passion for wanting to be an actress. She discouraged me.”

Years later, her friend and lyricist Marilyn Bergman suggested those early experiences steered Streisand towards the spotlight.

“If you don’t have a source of unconditional love as a child, you will probably try to attain that for the rest of your life,” she told her.

“That was a brilliant analysis,” reflects Streisand. “Very eye-opening.”

‘Dollar signs all over you’

Leaving home at 16, she took a job as a clerk, while working weekend shifts as a theatre usher, so she could keep up with Broadway’s latest shows.

“I got paid $4.50, I think it was, but I always hid my face because I thought someday I’d be well-known,” she says.

“Isn’t that funny? I didn’t want people to recognise me on the screen and know that I once showed them to their seats.”

The dream started to come true in 1960, when Streisand entered a talent contest at a Manhattan gay bar. The prize was $50 and a free dinner – and Streisand needed both.

She opened her set with the Broadway standard A Sleepin’ Bee. When she finished, there was a stunned silence, followed by rapturous applause. That night, the girlfriend of comedian Tiger Haynes told her: “Little girl, I see dollar signs all over you.”

She was right. Streisand was booked to play shows all around Greenwich, attracting celebrities, record labels and theatrical impresarios. One of them, Arthur Laurents, hired her for a small comedic role in the play I Can Get It For You Wholesale.

At the premiere, Streisand turned her single number into a standing ovation that reportedly lasted five minutes – but it was her next role that made her a sensation.

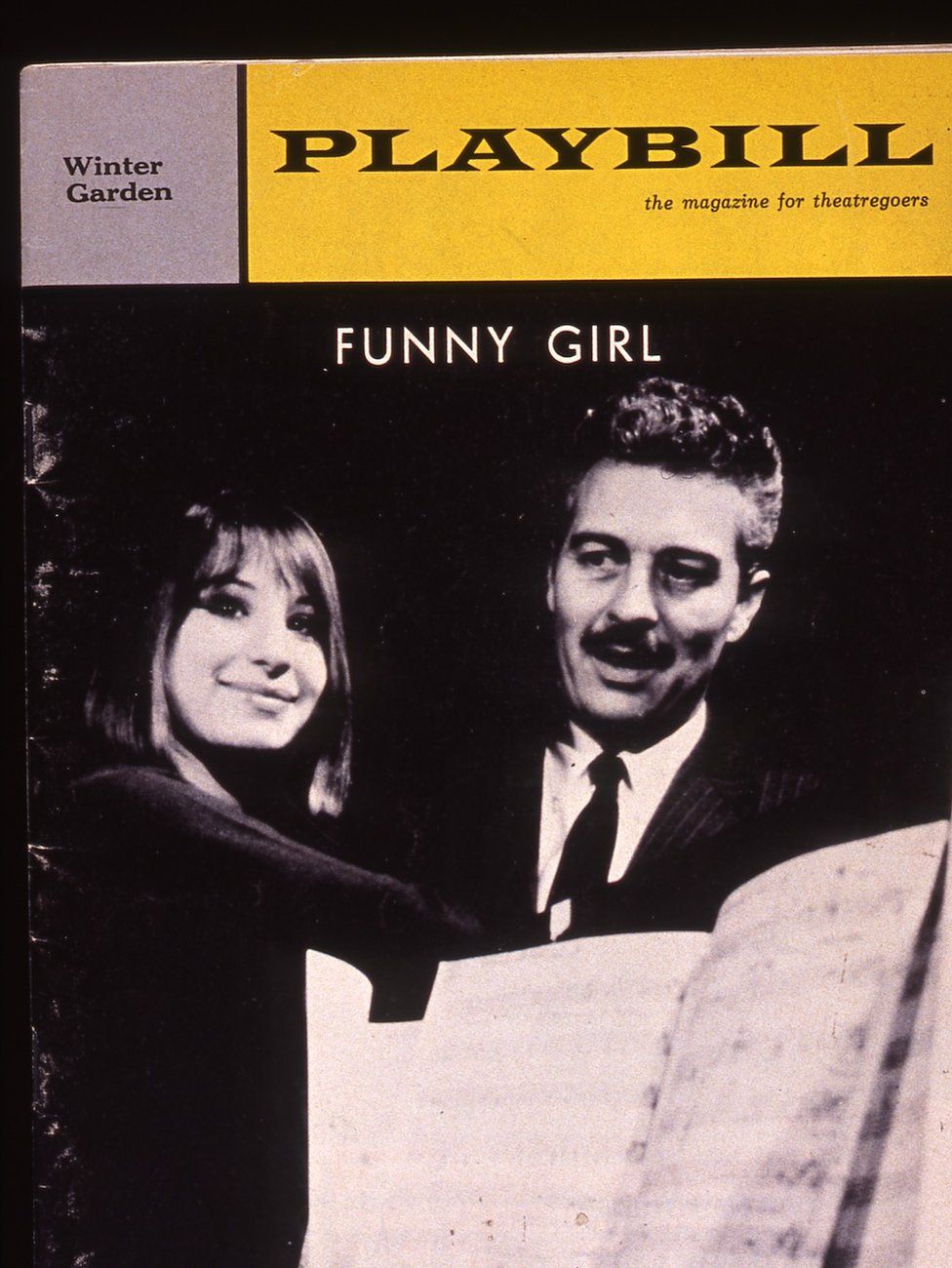

Funny Girl, loosely based on the story of vaudeville comedian Fanny Brice, was a once-in-a-lifetime marriage of actress and material.

Brice, like Streisand, was a young, Jewish woman who became a star through a combination of determination and hard work; who succeeded because of her differences, not in spite of them.

Blessed with songs like People and Don’t Rain On My Parade, the show earned rave reviews and eight Tony Award nominations, But Streisand couldn’t enjoy the success because her co-star Sydney Chaplin (son of movie star Charlie) was constantly trying to sabotage her performance.

“I don’t like to even talk about it,” she says, shaking her head at the memory.

“It’s just a person who had a crush on me – which was unusual – and when I said to him, ‘I don’t want to be involved with you’, he turned on me in such a way that was very cruel.

“He started muttering under his breath while I was talking on stage. Terrible words. Curse words. And he wouldn’t look into my eyes anymore. And you know, when you’re acting, it’s really important to look at the other person, and react to them.

“It threw me. Sometimes I thought, ‘What the hell is the next word?’ I felt so flustered.”

The experience contributed to the stage fright that stopped Streisand playing concerts for 27 years. But even when she quit live performance, male collaborators proved problematic.

Walter Matthau humiliated her on the set of Hello, Dolly, screaming: “I have more talent in my farts than you have in your whole body”; while Oscar-winner Frank Pierson publicly trashed the 1976 version of A Star Is Born – which he directed – calling Streisand a control freak who constantly demanded more close-ups.

The men who weren’t threatened by her confidence were entranced by it. Omar Sharif wrote long, passionate letters begging her to leave her husband; King Charles described her as “devastatingly attractive” with “great sex appeal”; while Marlon Brando introduced himself by kissing the back of her neck.

“You can’t have a back like that and not have it kissed,” he tells her.

“I think my heart stopped for a moment,” she recalls in the book. “What a line!”

In the 1960s and 70s, Streisand was unstoppable. As well as her movie musicals, she played screwball heroines in What’s Up, Doc and The Owl And The Pussycat, and the romantic lead in the hugely successful The Way We Were. In a parallel recording career, she scored hits like Woman In Love, Evergreen and No More Tears (Enough Is Enough), becoming the second biggest-selling female artist of all time.

She made her directorial debut with 1983’s Yentl – the first Hollywood movie where a woman was the writer, producer, director and star.

The story of an orthodox Jewish woman who disguises herself as a boy to study the Talmud, it was an allegory for sexual equality – making it all the more ironic when Streisand was paid nothing for the script, given minimum wage for directing, and forced to halve her acting fee.

But when she came to England for the film shoot, the sexism melted away.

“You had a Queen and Margaret Thatcher was the prime minister,” she says. “In other words, you weren’t intimidated by me being a woman.

“In America, I sadly tell you, it was so different. The people were cold, aloof.”

In print, Streisand takes the opportunity to settle those old scores and dispel the “diva” myth that surrounds her. She acquits herself well, telling a story of persistence and courage that’s laced with dry self-awareness and humour.

But she still has moments of star behaviour – such as the time she phoned up Apple CEO Tim Cook to complain that the iPhone was pronouncing her name wrong.

“My name isn’t spelled with a ‘Z’,” she protests. “It’s Strei-sand, like sand on the beach. How simple can you get?”

“And Tim Cook was so lovely. He had Siri change the pronunciation… I guess that’s one perk of fame!”

Now 81 years old, she suggests that the memoir is a full stop on her career. The film projects she pursued for the last decade – a biopic of photographer Margaret Bourke-White, and a movie of the musical Gypsy – have both fallen through.

Instead, she envisions spending more time at home.

“I want to live life,” she says. “I want to get in my husband’s truck and just wander, hopefully with the children somewhere near us.

“Life is fun for me when they come over. They love playing with the dogs and we have fun.

“I haven’t had much fun in my life, to tell you the truth. And I want to have more fun.”

Sign up for our morning newsletter and get BBC News in your inbox.